8

The work of Freud and Marx, along with some of their contemporaries, lays the groundwork for understanding Kenneth Burke’s theories of rhetoric. Freud’s identification theory and Marx’s dialectical theory heavily influenced Burke’s work.

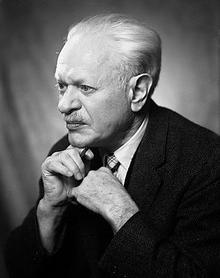

Kenneth Burke (1897-1993)

Kenneth Duva Burke was an American literary theorist, as well as poet, essayist, and novelist, who wrote on 20th-century philosophy, aesthetics, criticism, and rhetorical theory. As a literary theorist, Burke was best known for his analyses based on the nature of knowledge. Furthermore, he was one of the first individuals to stray away from more traditional rhetoric and view literature as “symbolic action.”

Burke was unorthodox, concerning himself not only with literary texts, but with the elements of the text that interacted with the audience: social, historical, political background, author biography, etc.

Burke developed the art of criticism, teaching at Stanford, Penn State, UCLA, and UC Santa Barbara. Hailed by The Johns Hopkins Guide to Literary Theory and Criticism as “one of the most unorthodox, challenging, and theoretically sophisticated American-born literary critics of the twentieth century,” the work of Kenneth Burke continues to fascinate American rhetoricians and philosophers. His prolific body of work, which consists of over 15 books, has influenced notable writers and critics such as Ralph Ellison and Harold Bloom. In 1981, Burke received the National Medal for Literature.

While teaching at Bennington College, Burke began to work on A Grammar of Motives (1945), outlining what he called “Dramatism,” his developing theory of language and literature. Professor William Rueckert of the University of Rochester, as quoted in the New York Times obituary for Kenneth Burke, described “Mr. Burke’s most notable achievement [as] the formulation of the systematic body of thought that he called ‘dramatism.’ The distinguishing characteristics of the dramatistic system are its inclusiveness, its reliance upon language (symbol-using) and its stress upon man’s capacity for moral/ethical action, which, according to Burke, is only made possible by language.”

Essentially, he believed that human actions reveal motives and values. He saw human beings as users of symbols and defined rhetoric as the moving of others through the use of symbols. He combined the theories of Freud and Marx with his own understanding of drama to create a rhetorical theory that would help people find better ways to communicate. Burke’s Identification Theory and his Dramatic Pentad form the basis for our modern understanding of rhetorical analysis.

Watch this video for an overview of Burke & his rhetorical theory:

Burke’s Theory of identification

The Pentad

In A Grammar of Motives, philosopher and critic Kenneth Burke presents a model for analyzing written and spoken language to better understand and even predict human behavior. His model, the pentad, can be used to understand or interpret human behavior and to develop ideas for stories. The pentad assumes people can have ambiguous, conflicting, and complex reasons for acting. It attempts to avoid simplistic explanations.

“[A]ny complete statement about motives will offer some kind of answer to these five questions: what was done (act), when or where it was done (scene), who did it (agent), how he did it (agency), and why (purpose).” –Kenneth Burke

The Fundamental Components of the Pentad

Like the journalistic questions, the pentad can be presented as a series of questions. By asking these fundamental questions, Burke proposes that we can generate insights about the factors that led us to the action. In particular, these questions will offer us insights into the following five components of a situation:

- The act

- The scene

- The agent

- The agency or method or means

- The purpose or motive

Relationships Among Terms

While analyzing specific acts or scenes can obviously lead us to some understanding about what motivated someone to do something, what really makes Burke’s pentad useful is his emphasis on the relationships among the terms. Burke is especially interested in the relationships, or ratios, that occur when the following terms are compared:

- Actor to act

- Actor to scene

- Actor to agency

- Actor to purpose

- Act to scene

- Act to agency

- Act to purpose

- Scene to agency

- Scene to purpose

- Agency to purpose

For example, by analyzing the “act-to-scene ratio,” we can gain information about how a scene, or social context, influenced the act. Thus, you might try to understand how criminal behavior is expressed in the inner city. If violence is an everyday part of the scene in a housing project in the inner city, then we can understand why residents might express a lot of fear about being a victim of violence. If we interviewed people in the community who acted violently (i.e., agents), then we might have a better sense of how they commit the violence (scene to agency) or why they believe they commit the violence (act to scene).

Watch this video for more information on Burke’s Pentad:

The Rhetorical Situation

A key component of rhetorical analysis involves thinking carefully about the “rhetorical situation” of a text. The rhetorical situation is another way to talk about the concepts covered in Burke’s Pentad.

You can think of the rhetorical situation as the context or set of circumstances out of which a text arises. Any time anyone is trying to make an argument, one is doing so out of a particular context, one that influences and shapes the argument that is made. When we do a rhetorical analysis, we look carefully at how the the rhetorical situation (context) shapes the rhetorical act (the text).

We can understand the concept of a rhetorical situation if we examine it piece by piece, by looking carefully at the rhetorical concepts from which it is built. The philosopher Aristotle organized these concepts as speaker, occasion, audience, and purpose. (SOAP). Answering the questions about these rhetorical concepts below will give you a good sense of your text’s rhetorical situation – the starting point for rhetorical analysis.

Speaker

The “author” of a text is the creator – the person who is communicating in order to try to effect a change in his or her audience. An author doesn’t have to be a single person or a person at all – an author could be an organization. To understand the rhetorical situation of a text, one must examine the identity of the author and his or her background.

- What kind of experience or authority does the author have in the subject about which he or she is speaking?

- What values does the author have, either in general or with regard to this particular subject?

- How invested is the author in the topic of the text? In other words, what affects the author’s perspective on the topic?

Occasion/Context

Nothing happens in a vacuum, and that includes the creation of any text. Essays, speeches, photos, political ads – any text – were written in a specific time and/or place, all of which can affect the way the text communicates its message. To understand the rhetorical situation of a text, we can identify the particular occasion or event that prompted the text’s creation at the particular time it was created.

- Was there a debate about the topic that the author of the text addresses? If so, what are (or were) the various perspectives within that debate?

- Did something specific occur that motivated the author to speak out?

Audience

In any text, an author is attempting to engage an audience. Before we can analyze how effectively an author engages an audience, we must spend some time thinking about that audience. An audience is any person or group who is the intended recipient of the text and also the person/people the author is trying to influence. To understand the rhetorical situation of a text, one must examine who the intended audience is by thinking about these things:

- Who is the author addressing?

- Sometimes this is the hardest question of all. We can get this information of “who is the author addressing” by looking at where an article is published. Be sure to pay attention to the newspaper, magazine, website, or journal title where the text is published. Often, you can research that publication to get a good sense of who reads that publication.

- What is the audience’s demographic information (age, gender, etc.)?

- What is/are the background, values, interests of the intended audience?

- How open is this intended audience to the author?

- What assumptions might the audience make about the author?

- In what context is the audience receiving the text?

Purpose

The purpose of a text blends the author with the setting and the audience. Looking at a text’s purpose means looking at the author’s motivations for creating it. The author has decided to start a conversation or join one that is already underway. Why has he or she decided to join in? In any text, the author may be trying to inform, to convince, to define, to announce, or to activate. Can you tell which one of those general purposes your author has?

- What is the author hoping to achieve with this text?

- Why did the author decide to join the “conversation” about the topic?

- What does the author want from their audience? What does the author want the audience to do once the text is communicated?

Worksheet

You may want to bookmark this worksheet on your computer, as it will help you as you write your own rhetorical analyses:

Attributions:

- Adapted from “What is the Rhetorical Situation?” by Robin Jeffrey and Emilie Zickel licensed under CC BY SA.

- “Burke’s Pentad” licensed under CC BY NC ND.

- “Burke” licensed CC BY.

- “Burke” licensed CC SA.